Program: #15-44 Air Date: Oct 26, 2015

To listen to this show, you must first LOG IN. If you have already logged in, but you are still seeing this message, please SUBSCRIBE or UPGRADE your subscriber level today.

The most recent efforts by Jordi Savall and his Capella Real de Catalunya venture into the Baroque: Monteverdi, Biber, and Magnificat settings by Vivaldi & Bach.

I. L’Orfeo (Alia Vox CD AVSA9911)

M. Figueras, A. Savall, F. Zanasi, S. Mingardo,

C. van de Sant, A. Abete, A. Fernández, D. Carnovich, F. Bettini

M. Hernández, M. Vargas, G. Türk, F. Garrigosa, C. Mena, I. García

La Capella Reial de Catalunya

Continuo : A. Lawrence-King arpa doppia

L. Guglielmi clavecin, organo di legno & regal, X. Díaz-Latorre théorbe & chitarrone

Le Concert des Nations

Direction: Jordi Savall

There are few myths in Greek mythology more obscure or more laden with symbolism than that of Orpheus. Extremely ancient in origin, it developed into a veritable theology around which an abundant and largely esoteric literature developed. Orpheus is the “singer” par excellence, the musician and the poet. He played not only the lyre with admirable skill, but also the zither, the invention of which is attributed to him. It was said that the airs he sang and played were so sweet that wild beasts followed in his train, trees and plants bowed down to him and the fiercest of men were totally subdued by his music.

Virgil (70-19 BC), in Book IV of The Georgics, gives us the richest and fullest version of one of the most celebrated myths about Orpheus: his descent into the underworld for the love of his wife, Eurydice, who had died of a snakebite while fleeing from the pursuit of Aristaeus. With his singing and the strains of his lyre, Orpheus managed to charm not only the monsters of hell, but also the gods of the underworld. Poets have vied in their attempts to describe the effects of this divine music. Finally, the gods of the underworld yielded to Orpheus’s entreaties, but they did so on condition that he retrace his steps to the light of day, followed by Eurydice, without turning to look at her before leaving their kingdom.

But just as he was about to complete his journey, Orpheus was seized by a terrible doubt: What if he had been deceived? Was Eurydice really following him? He turned round suddenly, and Eurydice died a second time. Orpheus tried to go back for her, but this time Charon was unyielding and the inconsolable Orpheus was forced to return to the world of human beings. Among the many attempts to set this myth to music, the most accomplished and complete is La favola d’Orfeo on a poem by Alessandro Striggio with music by Claudio Monteverdi, which was first performed at the court of Mantua on 24th February, 1607. Thanks to its extraordinary musical and dramatic conception and its carefully crafted score, Monteverdi’s Orfeo attains a perfection almost unparalleled in the entire history of opera. Following some early experiments on a similar theme, such as Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini’s Eurydice to a libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini (Florence, 1600), Monteverdi’s first opera marks the true beginning of the spread of the new stile rappresentativo. Monteverdi was the first musician to give absolute priority to the expression of feelings “che movono grandemente l’animo nostro” (which greatly move our spirit), to the portrayal of passions. Thus, in asserting that “the modern composer must base his works on truth,” he was defining a revolutionary, radical concept that would irreversibly alter the relationship between text and music. His work singles him out as one of those very rare polyvalent geniuses who are endowed with the ability to synthesize the most diverse styles. Monteverdi is unquestionably a Baroque composer, but his music contains all the essential ingredients found in later musical ideals.

He is brilliantly defined in the following eloquent text by Harry Halbreich:

“What is a Romantic artist? A Romantic artist is one who puts expression above form and inquiry; an artist who above all strives to translate the feelings and passions of his characters through the prism of his own personality: such is Monteverdi.

What is a Classical artist? A Classical artist is one who refuses to sacrifice pure beauty, equilibrium and harmony of proportions; an artist who creates new forms and means of expression which will be taken as a model by the generations that come after him: such is Monteverdi.

What is an Impressionist artist? An Impressionist artist is one who gives subject, colour and harmony a distinctive value in their own right, one who believes that the senses must be satisfied, just as the mind and heart must be satisfied: such is Monteverdi.

What is a Modern artist? A Modern artist is one who engages passionately with the age in which he lives, constantly contributing to its progress by exploring and conquering his own sensibility and expression; a musician who remains forever young: such is Claudio Monteverdi, a composer who will always be our contemporary.”

Today, more than 400 years after they were composed, Orfeo and Monteverdi’s other two surviving operas continue to be living works with a capacity to touch and move us at the deepest level of our sensibility, as witnessed by the works’ increasing popularity throughout the world and the growing interest they arouse. In this Orfeo we experience the power of music in one of its purest, most concentrated forms. —Jordi Savall

II. Biber: Missa Salisburgensis (Alia Vox CD ASVA 9912)

H. Bayodi-Hirt, M.B. Kielland, P. Bertin, D. Sagastume, N. Mulroy, Ll. Vilamajó,

D. Carnovich, M. Scavazza, A. Abete

La Capella Reial de Catalunya · Hespèrion XXI · Le Concert des Nations

JORDI SAVALL

1. FANFARA

Bartholomäo Riedl (ca. 1650-1688)

2. Motet : PLAUDITE TYMPANA, à 54 (1682)

BATTALIA, à 10 (1673)

3. Sonata 1’44

4. Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor: Allegro

5. Presto

6. Der Mars

7. Presto

8. Aria

9. Die Schlacht

10. Lamento der Verwundten Musquetirer: Adagio

11. SONATA SANCTI POLYCARPI, à 9 (1673)

[] - Allegro - Allegro – Presto

MISSA SALISBURGENSIS, à 54 (1682)

12. Kyrie

13. Gloria

14. Credo

15. Sanctus - Benedictus

16. Agnus Dei

Like a great, mysterious nebula, the dazzling Missa Salisburgensis arches over the world of polychoral music by virtue of the exceptional complexity and richness of its means, which are deployed to create a unique expression in sound and space, symbolising with extraordinary exuberance and efficiency all the strength and grandeur of divine power, political and religious power. Shrouded in mystery and regarded by specialists as the Everest of polychoral compositions, this work was discovered by a Salzburg grocer in 1870. At first it was mistakenly attributed to the composer Orazio Benevoli, but now, as Professor Ernst Hintermaier explains (see his accompanying commentary), it is unanimously considered to be among the masterpieces of Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, one of the greatest and most talented Austrian composers of the Baroque period.

More than 15 years ago, I was fortunate to have my first experience performing Biber’s sacred music. It was in late May 1999, and I was preparing a concert featuring the Requiem and the Missa Bruxellensis XXIII vocum to be given at Salzburg Cathedral during the Pfingsten Barock Festival. This event provided me with the opportunity to acquire a profound understanding of the complexity of Biber’s polyphonic and polychoral style and, most importantly, to experience it in the acoustic conditions of the cathedral where Biber’s works had received their first public performance during the composer’s lifetime. Thanks to the intense work carried out, we were able to take the opportunity afforded by the concert to make the first live recordings of the Mass as well as the Requiem, two unique versions which we released under our label Alia Vox in 1999 and 2002, respectively.

Fifteen years later, in 2014, we were invited to the Konzerthaus in Vienna during the Resonanzen Festival to perform Biber’s other great Mass, the Missa Salisburgensis à 54 (Vocum), one of the pinnacles of sacred music of all time, and the motet “Plaudite tympana,” which were also composed to mark the 1100th anniversary of the foundation of the archbishopric of Salzburg by St Rupert. To complement the programme we have selected Bartolomaus Riedl’s slightly earlier Fanfares, together with Biber’s Sonata Sancti Polycarpi à 9 and his Battalia à 10, composed in 1673.

The invitation spurred us to prepare the works at home in Catalonia, where we performed them at the Auditori in Barcelona just a few days before the concert at the Konzerthaus in Vienna. We spent several days at Cardona Castle, rehearsing and at the same time working on the sound balance, preparing the recording and experimenting with spatial dispositions in the fine acoustics of the Romanesque chapel. After this period of intense preparation, we gave our first performance of the works at the Auditori in Barcelona on 15th January 2015. On 16th January we returned to Cardona for a final recording session before leaving the next day for Vienna, where on 18th January we performed the complete programme for a second time at the city’s Konzerthaus.

Despite our intense experience of performing Biber at Salzburg Cathedral in 1999, and taking into account the complexity of Biber’s polyphonic music, I must confess that I approached the preparation of the Missa Salisburgensis with a great deal of respect and the utmost care in relation to the exceptionally large number of parts (54) to be kept under control, bringing out the music’s extremely complex counterpoints and, above all, the conditions necessary to achieve the right spatial balance in the layout of the various, highly contrasting ensembles or choruses of voices and instruments so clearly envisaged by the composer himself:

Chorus 1. 8 soloist Voices in concert and Organ

Chorus 2. 6 Strings [2 Violins, 2 Violas, 2 Viols]

Chorus 3. 2 Oboes, 4 Flutes [2 Flutes, 2 Dulcians], 2 Clarino trumpets

Chorus 4. 2 Cornetti, 3 Trombones)

Chorus 5. 8 soloist Voices in concert

[Chorus 6.] 6 Strings [2 Violins, 2 Violas, 2 Viols]

1. Loco. 4 Trumpets, Timpani

2. Loco. 4 Trumpets, Timpani

Organ

Basso Continuo (Cello and Violone)

This exceptional line-up serves to remind us that the archbishopric of Salzburg was one of the leading centres of the ancient Roman and Venetian traditions. Having embraced them, it then went on to transmit them after embellishing them in many respects. The vast acoustics of Salzburg Cathedral demanded a style that avoided excessively rapid harmonic changes and highly individual ornamental refinements.

On first hearing the work, therefore, one might be surprised by the inevitable, dominating presence of the C major key of the trumpets; however, as Paul McCreesh (the founder and director of the Gabrieli Consort & Players) observed, on listening more carefully we discover a very subtle structure and some surprising harmonic shifts, which are all the more remarkable in that they occur during a sumptuous pasaje in C major, as well as a rich abundance of motifs in the ground bass. A simple, popular musical figure features in the development of much of the melodic material, as well as the novel effects in the Benedictus and the Agnus Dei, with its poignant a capella polyphony in the Miserere and especially the great richness of figures which unfold in the Gloria in excelsis Deo and the Credo. We are enthralled by the breathtaking emotion and guileless beauty of the Incarnatus, sung by the six high voices, and, in stark contrast, the deep sorrow conveyed by the Crucifixus, sung exclusively by the deep voices.

For the recording we positioned the various choruses in the chapel of Cardona Castle so as to recreate the same spatial conditions and instrumental layout used in Salzburg Cathedral: Basso continuo (cello and violone) in the centre, flanked on either side by the two choirs of voices in concerto (choruses 1 and 5), consisting of 8 solo voices, each one accompanied by an organ; opposite and mirroring each other, the two string ensembles (choruses 2 and 6); behind the vocal ensembles, to the right, 2 cornetti and 3 sackbuts (chorus 4) in an allusion to Venice, and to the left 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 dulcians and 2 clarini (chorus 3), which are distinguished by their flexibility and high-pitched harmonics from the more military sound provided by the two choruses of trumpets and timpani (Loco 1 and 2), which are placed at either end of the church (at the altar and at the far end of the building) to provide a powerful punctuation to the various sections of the Mass and the Motet. These instrumental ensembles link heaven and earth: blazing fanfares to the glory of God, celebrating the power and magnificence of an ancient church and a city-state at the core of political power in a country at the German heart of the old Holy Roman Empire of central Europe.

Difficult though it is to imagine how the people of Salzburg might have reacted to this truly stunning “musical nebula” in 1682, it seems likely, as Reinhard Goebel (the founder and director of Musica Antiqua Köln) speculated, “that they were undoubtedly as moved and spellbound as we – and in particular, we, the performing musicians – are today.” Whatever the case may be, this music demonstrates that Salzburg had nothing to envy Rome or Venice. The Baroque splendour of the archbishopric calls to mind the symbolic image of the heavenly Jerusalem, with its myriad spires and hosts of cherubim singing the eternal praises of a heavenly life bearing a new message of peace and the promise of universal redemption. —Jordi Savall

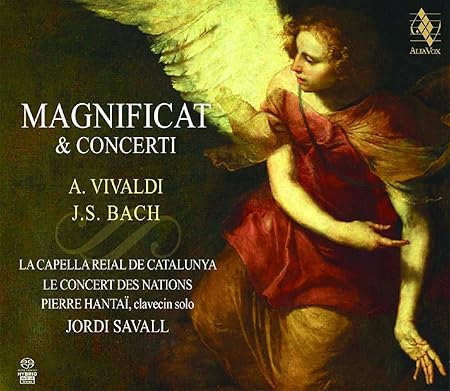

III. Magnificat & Concerti—Vivaldi & Bach (Alia Vox CD AVSA 9909D)

Solistes

Hanna Bayodi-Hirt, Johannette Zomer soprano

Damien Guillon contreténor David Munderloh ténor

Stephan MacLeod baryton

La Capella Reial de Catalunya

et participants sélectionnés de la IIIe Académie 2013

Le Concert des Nations

Pierre Hantaï clavecin

Manfredo Kraemer, Pablo Valetti violini concertanti

JORDI SAVALL

viole de gambe et direction

ANTONIO VIVALDI

Concerto con 2 violini e “Violoncello all’Inglese”[viola da gamba] Archi e Continuo (Sol minore RV578 [1725])

1. Adagio e spiccato – Allegro

2. Larghetto

3. Allegro

Magnificat en Sol mineur RV 610

4. Magnificat Adagio

5. Et exultavit Allegro

6. Et misericordia eius Andante molto

7. Fecit potentiam Presto

8. Deposuit potentes Allegro

9. Esurientes Allegro

10. Suscepit Israel Largo

11. Sicut locutus est Allegro ma poco

12. Gloria Patri Largo

13. Sicut erat in principio

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Concerto pour clavecin en Ré mineur BWV1052

14. Allegro

15. Adagio

16. Allegro

Magnificat en Ré majeur BWV 243

17. Magnificat Choeur

18. Et exultavit Soprano II solo

19. Quia respexit Soprano I solo

20. Omnes generationes Choeur

21. Quia fecit mihi magna Basse solo

22. Et misericordia Alto solo & Ténor solo

23. Fecit potentiam Choeur

24. Deposuit potentes Ténor solo

25. Esurientes implevit bonis Contralto solo

26. Suscepit Israel Soprano I & II & alto

27. Sicut locutus est Choeur

28. Gloria Patri Choeur

J. S. Bach’s Magnificat, the choral music of Tomas Luis de Victoria, the third Sonata for Viola da gamba and Harpsichord and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem belong to the earliest musical experiences of my childhood and teens. Those first encounters made such an impression on me and illuminated so clearly the future direction of my life, that sometimes it is as if I were still searching for those ineffable pieces of music that gave me so much joy at that time in my life.

At the age of six, when I began training as a chorister at the religious school in Igualada, I gradually discovered along with the other children the beauty of Gregorian chant and the wonderful music of Tomás Luís de Victoria and other Golden Age masters. I can also still remember as if it were yesterday the powerful impression made on me when I first listened to a recording of J. S. Bach’s Magnificat and, almost simultaneously, Bach’s third Sonata for Viola da gamba and harpsichord performed by Pau Casals on the cello and Mieczysław Horszowski at the piano (at that time I didn’t even know that it was a work for viola da gamba!) It was the end of a swelteringly hot summer, and at the age of 10 I was slowly recovering from a serious typhoid infection from which I very nearly died. During the two months of my long convalescence, the only personal happiness I enjoyed was reading a little and, above all, listening to music on my little radio all day long. I was immediately and permanently overwhelmed by the beauty of those performances and even more so by the intense emotion radiating from those old scores by Bach. After battling against serious illness, day by day I began to experience the benefits of music for both my body and my soul. It was truly staggering to realize that those powerful works, created and performed by mortal human beings, have become immortal masterpieces, thanks to their beauty and depth of emotion.

Five years later, in 1956, while listening to a rehearsal of Mozart’s Requiem accompanied by a string quartet at the Conservatoire in Igualada, I was so overcome by the power of the music that I made up my mind there and then to become a musician. I chose the cello and for the first time in my life I embarked on a path of self-study and work that was a source of great happiness. For nine years I studied eight hours a day, and after finishing my studies at the Conservatoire in Barcelona in 1965, I discovered the viola da gamba and fell in love with this neglected instrument. Totally fascinated by early music, I set out on my pilgrimage to the great music libraries, a journey which took me from Barcelona to Paris, London, Brussels, Bologna, Madrid, etc., and after three years of studying by myself, I was accepted to study with August Wenzinger at Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel. The rest is common knowledge… It is a truly miraculous moment when you realize that you have found your way and a home in life. Mark Twain was right when he said, “The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why”, because from that moment on, life becomes the most wonderful and stimulating experience.

Could it be that adult life is just a quest for the happiness we felt when we were pure, innocent children? Making music is also about seeking and developing a particular way of life… A life that can only blossom through seeking and sharing beauty and happiness.

This reminds me of the wild strawberries in a beautiful Zen story: “A man was calmly walking in the forest when suddenly a tiger appeared and began to chase him. He ran and came to a precipice and started to climb down; he thought he was safe, but when he looked at the bottom of the precipice, he saw that there was another tiger waiting there. He paused, not knowing what to do. Then suddenly, seeing some wild strawberries growing near him, he picked them and began to eat them, saying to himself: How delicious these wild strawberries are!”

The wild strawberries of the story may be the work we are passionate about, or anything that we decide to do with relish and concentration: singing, working in the garden, writing, mountain climbing, playing a piece of music, or listening to J. S. Bach’s Magnificat... In other words, it is knowing how to find happiness in whatever we do, and if we do it well, then all the tigers, both those lurking within us and those we imagine to be outside us, vanish. And then life begins to be much more beautiful. —Jordi Savall

Composer Info

Claudio Monteverdi, JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH, ANTONIO VIVALDI, Bartholomäo Riedl (ca. 1650-1688), Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber,

CD Info

CD AVSA9911, CD ASVA 9912, CD AVSA 9909D.